Trouble in Enlightenment

Woke does not stem from institutional capture but a crisis of purpose within

This is the third in a three-part series on the culture wars in museums. Click here to read part 1: From Enlightenment in Atonement'; and here to read part 2: The Birth of the Public Museum.

***

When in the late 1980s the repatriation of human remains became a prominent campaign in the US, few Native American tribes showed much interest in becoming involved. There were activists, including Vine Victor Deloria Jr., but in number and in force of argument those agitating for return and burial were museum professionals or academics in related fields.

Anthropology professor Russell Thornton, who was working at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, recalls that when the museum first contacted tribes about repatriation, most Native groups did not respond because they were ‘generally focused on local issues’. Nonetheless, the museum persisted.

The anthropologist David Hurst Thomas describes how the Smithsonian anthropologist Ted Carpenter travelled to Greenland to bury the remains of four individuals from an Inuit group. Eventually, the pastor of the group agreed to bury the remains, but only after he had been pressured to do so by a Danish bishop.

When Carpenter asked a member the Inuit's what they felt about the repatriation and burial service, they replied: “Embarrassment.” Carpenter concluded: “The whole service was really for us”. The Inuit were participating out of courtesy to the anthropologists. Hurst Thomas also suggests that the Inuit reluctance may have had something to do with the fact that their religion attributes evil properties to the dead.

In the main, it was museum professionals making the case to repatriate valuable human remains from their collections. Why? Because the debate over human remains and the museum’s role is an internally driven problem: it is not something that has come from people agitating outside museums or as a result of institutional capture. No closet Marxists have stormed the institution to shove human remains out of the cupboards.

Instead, the repatriation of human remains, and related later campaigns like decolonisation, is a response to a profound crisis of legitimacy that has been building for decades and for which woke serves as a temporary answer. A cohort of museum professionals are distancing themselves from the older sources of legitimacy and purpose, those forged with enlightenment principles of the pursuit and dissemination of knowledge, and searching for a new one.

Trouble in Enlightenment

After the carnage of the Second World War, the Holocaust, and the atomic bomb, perceptions of rational enquiry and science changed dramatically. Scientific inquiry, which once held authority, came to be viewed less as a method from which advances in medicine and society could be furthered and more as a potential hazard.

With the rise of postmodern and post colonial theories, science came to be viewed as reflection of the local prejudices of European cultures rather than universal and objective. Science, as the philosopher, Sandra Harding, put it is “politics by other means”. These ideas, popular in academic circles, filtered through into society.

At the same time, discussions about seizing the means of production were falling silent. Rather than more structural and material change, which many people believed had failed, political activists on the left started to think that changing the culture and language was the way forward. They started to target the media, language and cultural institutions as vehicles for change.

The New Museology

Until the 1980s, most of writing on museums within the profession and by academics was devoted to reports of exhibitions, discussion about equipment: the best lighting for a display, what type of glass and wood to use for the cabinets, and histories of collections. There was some examination of museums' social and educational role, but it was minimal.

That changed irrevocably in the late 1980s, when a huge body of work emerged that tore into the idea that museums were value-free and argued that they are inherently and unavoidably political. It was self consciously called “the new museology”; the use of the “new” explicitly trying to distance the profession from the old way of doing things.

The development of museums in Western societies, it came to be argued by a wide group of museologists and practitioners, occurred in specific historical circumstances and actively supports the dominant classes, maintaining the status quo as natural. “The New Museology specifically questions traditional museum approaches to issues of value, meaning, control, interpretation, authority and authenticity.” summarised the historian Deirdre G. Stam.

The cultural theorist Stuart Hall argued that museums and cultural institutions should be constantly interrogated. The institution:

“Its purpose is to destabilise its own stabilities.”

With the decline and critique of Enlightenment values within intellectual thought, and the rise of relativism and mysticism and post-colonial theory, the traditional justifications of the museum were interrogated and challenged from within.

Those who did not feel this way were half hearted in their response or failed to appreciate the strength and power of these new ideas coursing through museums and museum studies courses - and training new generations of curators in anti-museum think.

Repatriation as a New Purpose

The debate over human remains all began in the late 1980s, in North America and Australia, when indigenous campaigners and radical anthropologists argued that the thousands of human remains remains held by museums should be returned to affiliated communities.

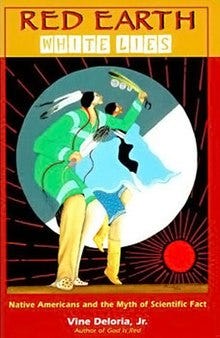

The Native American scholar and activist Vine Deloris Jr., argued in Red Earth, White Lies: Native Americans and the myths of scientific fact that science is only a “myth” which sidelined Native American theories: “the scientists have maintained a strangle hold on the definitions of what respectable are reliable human experiences are”.

Campaigners for return, including Cressida Fforde then from the Institute of Archaeology at University College, London, too put forward these ideas, and argued the scientific study of human remains was itself a means of colonial domination.

In The Dead and their Possessions: Repatriation in Principle, Policy and Practice, Fforde advanced that knowledge was an assertion of power. Drawing a direct link between colonial authorities and contemporary scientists, Fforde described how the studying human remains “constructs the identities of both the superior coloniser and the inferior native”.

“Repatriation and reburial”, Fforde writes, "are loci for processes which both construct and reaffirm Aboriginality, empowering its participants by enabling them to assert, define (and thus take control over) their own identity”.

Scientists vigorously objected to returning human remains to the communities deemed affiliated to the remains, who often buried them. As in the case of the Kennewick Man: a 9,300 year old skeleton found on the banks of the Columbia River in Kennewick, Washington, on July 28, 1996. In 2017, after 20 years of legal battles and scientific study, he was reburied in the high desert of the Columbia Plateau, and is no longer available for research. The scientists found that their arguments - for knowledge and for history, even for helping people to understand the origins of past civilisations - were too abstract against the moral urgency of righting past wrongs and identity affirmation in the present. Science and research into the lives of past peoples was seen as damaging not enlightening.

Human Remains are Potent Objects

Human remains are potent objects. They aren't simply like a pot, vase, or other museum material; they were once human beings and evoke strong feelings and reactions. It's one reason why they can be so popular when on display. People find them fascinating if also unnerving. Additionally, the graves of indigenous people were robbed in the past when the authority of science held sway.

But that also means they can be used like lighter fluid in political and cultural claims. In The Political Lives of Dead Bodies, the anthropologist Katherine Verdery analysed the burial or exhumation of dead bodies in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union and draws lessons of this. She observes that human remains are useful symbolic objects because they are ambiguous - there is no one meaning - and yet, at the same time, appear to be associated with life, death and the sacred. Political actors use them, she says, because they seem to have a fixed meaning, but "words can be put in their mouths.”

UK Human Remains Debate

Debates over the future of human remains coursed through the British museum profession in the late 1990s. But the issue's prominence was curious: there is no indigenous population in the UK, and British museums hadn't received many requests for return. A 2003 survey conducted by the DCMS Human Remains Working Group described claims from overseas indigenous groups on institutions as "low". There were only 33 such requests on English institutions, seven of which had already been agreed to and some of which were repeat claims from the same group. One of the requests for repatriation came from the curator himself.

Undeterred by the small number of claims, many in senior positions in the museum world argued for repatriation as a priority for the museum world. As when in 2003, the director of Manchester Museum pushed to repatriate skulls in the collection to indigenous people in Australia. “The collections in our Western museums derive, at their most innocent, from grave robbing, and at their worse, from wholesale slaughter,” the scientifically trained professional said in a public debate. Urging repatriation, he argued, continuing: “We now have the opportunity to redress that historic imbalance [of power], acknowledging that this may well mean a loss to science.” The loss to science was the point.

As in the US, opponents to repatriation quickly found that the argument for what scientific research can tell us about past people held little sway. Additionally, in the UK, scientists who objected to the repatriation of human remains as destroying unique evidence often relied on the law in their arguments, which had said it was not permissible under the terms of the British Museum Act of 1963. (The same Act which prevents the British Museum from deaccessioning the Elgin Marbles). But that campaign became redundant when in 2004, lawmakers removed the clause that applied to human remains. The law was no longer a barrier. Their argument was no longer relevant.

Because very quickly profession concluded that repatriation of human remains was the right thing to do. Doing so was a way of showing that museums were changing. They were not like the old institutions that advanced knowledge to the detriment of communities. It gave them energy and zeal. It was invigorating.

One campaigner for repatriation that I interviewed, a senior archaeologist at a museum, argued that museums needed to change, and that they should play a different role to that of their past:

“Museums have to grow up… be less concerned with where things are and less concerned with maybe issues around control and authority”. Instead, he said, they should “make sure that artefacts or other material over which the museum has responsibility are in a position where they can do most good”.

Another curator explained to me:

The campaign to return human remains gave this professional meaning: it gave him purpose and mission.

“Nearly All the Museums Human Remains are Gone”

So writes the archaeologist Chip Colewell, in Plundered Skulls and Stolen Spirits: Inside the Fight to Reclaim Native America's Culture, his insiders account of being the senior curator of anthropology at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, where he repatriated hundreds of human remains to federally approved affiliated communities.

In particular, Colewell celebrates burying the human remains for which he could not find a tribe to take; what he called “orphaned" remains, which could have stayed on the shelves to be studied or saved for later investigation.

It is Colewell’s “fleeting moment of satisfaction” about orphaned remains - the ones no tribe wants - that tells us something. This personal identification with the problem of human remains speaks to its symbolic nature. Many within the sector are searching for a new role, and the old way – researching the past and presenting that research to the public – is no longer considered valuable. Burying human remains demonstrates that.

And it is for this reason that I predict arguments over museums, such as that stimulated by the Wellcome Collection last autumn, when it shut its Medicine Man gallery because it was “racist, sexist and ablest”, and deliberately and asked ‘What is a Museum?” as a provocation - is not going away, despite many thinking it might. That question - posed as a critique - has been around for a while and will not be resolved because asking the question and critiquing the past is the default approach.

When the purpose is, in Stuart Hall’s words, “destabilise the stabilities” there is no end point. Critique is a permanent state of affairs. Removing items from the shelves, and closing collections down is the main option open to members of the profession. Unless there are those who can once again find a purpose rooted in rational inquiry and the collection and display of artefacts of past human civilisations. Unless we can rediscover the enlightenment purpose of the museum.