To illustrate the shift in the enlightenment museum to one that is anti-enlightenment, it is best to start at the beginning. This post, the second in the series on the roots of the culture wars in museums, looks at the birth of the public museum in the Age of Reason.

When the British Museum opened in doors in 1759, there were no Elgin Marbles or Roman statues. There were no Mesopotamian beasts or monumental pink granite Egyptian pharaohs. There was a strange piece of coral in the shape of a human hand, a shoe made of human skin, and ear ticklers from China.

It was formed out of the sprawling collection of Hans Sloane, who had been born in Ulster in 1660 to a Catholic working-class family. He became a physician, tending to the royal family and the great and the good, assisting philosopher John Locke with his diabetes. He advised Westminster and the Crown on national health matters, and promoted inoculation against smallpox. He traveled to Jamaica where he was a plantation doctor, and he made his fortune through investment in land and slavery.

He was also an impressive natural historian, in his words: “very much pleas’d with the study of plants, and other parts of nature”, succeeding Issac Newton as the President of the Royal Society. And during his travels and his long life, he accumulated hundreds and thousands of interesting objects.

Sloane’s collection was initially informed by Renaissance ideas about assembling the world in microcosm.

Museums had emerged from a transformative period in intellectual and political life, during the foundations of early modern Europe. By the end of the 16th century, establishing what was known as a kunstkammer, galleria, or wonderkammer, was common in European courtly circles.

Cabinets of curiosities, as they are collectively called, upheld the glory of God and man’s place within his creation. They tried to manage and make sense of the enormous amount of material flowing out from the Renaissance study of ancient texts, as well as the Voyages of Discovery.

Rudolf’s Wonderous Kunsthammer

“The Emperor is a lover of stones, and not simply because he hopes thus to increase his dignity and majesty, but through them to raise awareness of the glory of God, the ineffable might of Him who concentrates the beauty of the whole world into such small bodies and in them unites the seeds of all other things in creation.”

So wrote alchemist and court physician to Rudolf II, Anselm Boethius de Boodt, in 1609, wrote about Rudolf II’s wonderous kunsthammer.

Rudolf II - the Holy Roman Emperor, king of Hungary and Croatia, and archduke of Austria - stuffed his acclaimed collection, at the heart of his empire in Prague castle, full of the wonders of the age: antiquity, ivory, books, paintings by Leonardo da Vinci, sixty clocks, 403 Indian curiosa, 120 astronomical or geometric instruments, musical instruments, uncut diamonds and antlers.

State visitors were shown Rudolf’s collection as a demonstration of his magnificence and power. Such a collection, it was thought, could form a microcosm that could be manipulated ‘pantongraphically’ - it could influence the real world. It also started to be visited by artists and travellers.

Whilst at first, the collections of princes and powerful persons were only open to the most powerful, and located near the main parade rooms in palaces, as knowledge became more about being open - and testable - than closed, they were made more available.

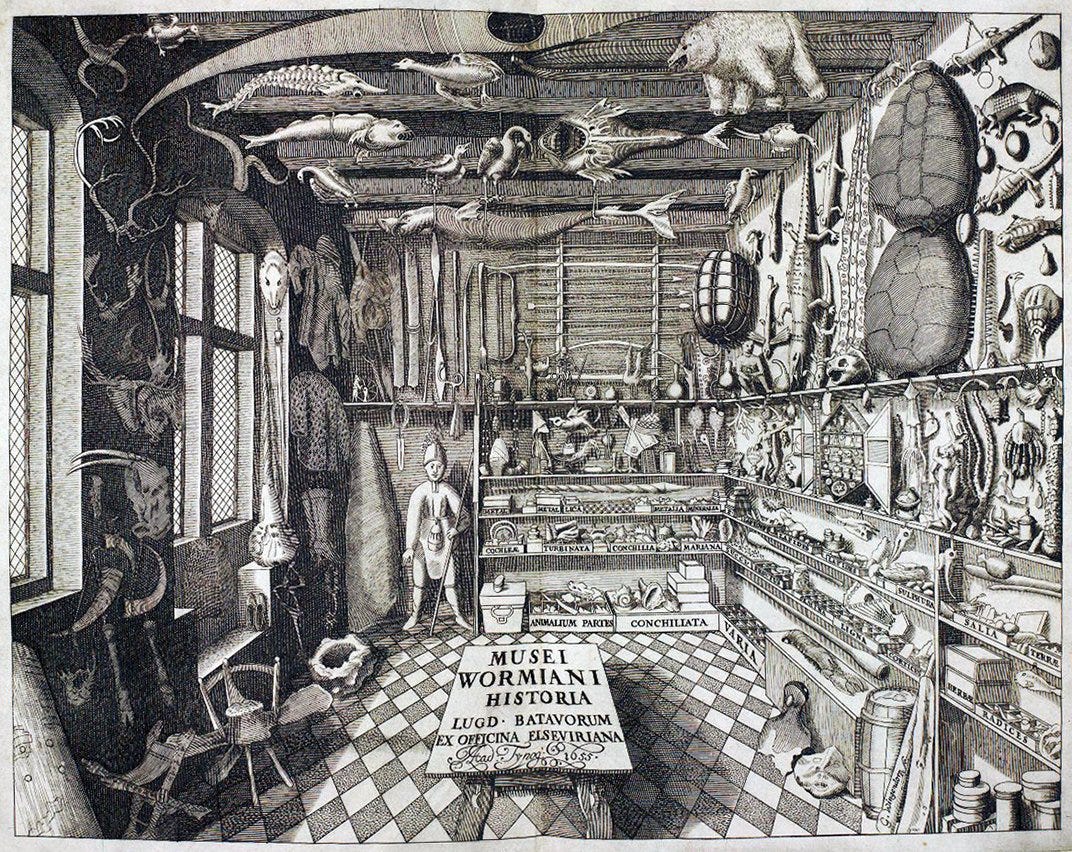

Old Worm’s Museum

One renowned 17th century cabinet, in Copenhagen, belonged to Old Worm, a Danish physician and antiquarian, who had made made advance in embryology - the study of the formation and development of an embryo and foetus. ( The wormian bones are named after him.)

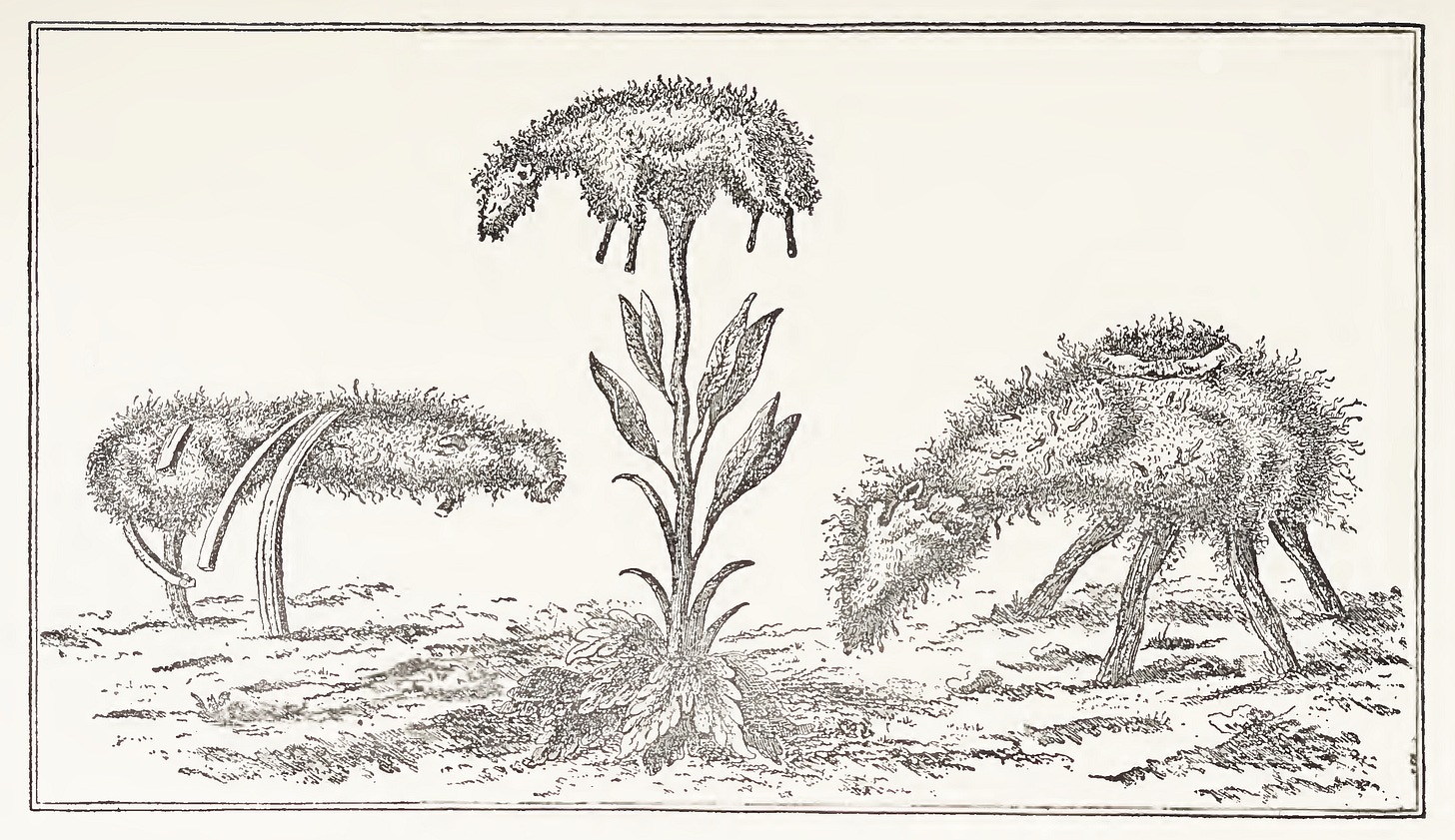

Old Worm’s collection of artefacts from the expeditions to the new world straddled the premodern and modern period. He encouraged his students to make observations and discoveries about the objects through direct handling and study, rather than relying on old myths or the theories of earlier writers. He proved that the unicorn did not exist, by showing that what people thought was its horn actually came from a narwhal. But he also believed he had a Scythian lamb: a half fern and half sheep.

From Wonder to Enlightenment

Hans Sloane was no secular radical. He wanted to build a collection to understand God’s intentions and design better. On his travels, he collected hundreds of plant and animal specimens: a live alligator, fossils, amulets, coins, medals, and manuscripts, all for this purpose. He brought back stringed instruments played by enslaved Africans on Jamaica and wrote down the music they played. Though he acquired no saintly relics he did hold out hope that he would find a unicorn, despite Old Worms efforts to discredit their existence.

He also swallowed the entire collections of many other collectors and and was lampooned for his capacious and disordered collecting habits. One critic said that Sloane peddled “Nicknackatory”; another described him as “the foremost toyman of his time”; another, described his collection as, ‘a matter of only scraps’.

When Sloane died in 1753, at the ripe of age of 93, he bequeathed his collection of 80,000 “natural and artificial rarities” to King George II for the nation, in return for £20,000 for his heirs, and on condition that Parliament create a freely accessible public museum to house it.

Itemised records show that it included 32,000 coins and medals, 268 seals, 173 star fish, 521 vipers and serpents, 50,000 books prints and manuscripts, a herbarium of 334 columns of dried plans, and 1,125 “things relating to the customs of ancient times”. It also included the coral in a shape of a human hand, the shoe made of human skin, and ear ticklers from China.

It was the founding collection of the British Museum.

With the British Museum, cabinets of curiosities were transformed from their private, seemingly eclectic and confused assemblages, into taxonomically ordered displays for the public.

Improving the Knowledge of All Studious and Curious Persons

The British Museum opened its doors Monday, 25 January 1759, in Montague House, a 17th century mansion on the site of today’s building in Bloomsbury, free of charge to “all studious and curious persons”, “for the improvement knowledge and information of all persons”.

The unprecedented open access policy caused consternation. Lord Cadogan had urged admission be denied to “very lower & improper persons, even menial servants,” but was disregarded. Anxieties about unruly audiences, who had to apply in writing and have clean shoes, lingered.

“The company was various, and some of all sorts…[including] the very lowest classes of the people,” the German author, Karl Philipp Moritz, noted when visiting the BM in 1782, “for, as it is the property of the nation, every one has the right (I use the term of the country) to see it.”

Children were forbidden until 1837.

The British Museum was the first public institution to use the prefix “British”. It was probably intended to embody the values of the new state, which had been created in 1707 in a political union between England and Scotland. It was also formed in opposition to the French idea of royalty. ‘British’ meant belonging neither to the Church nor to the king, but to the citizenry. A nation was being imagined. Though there was nothing initially in the museum that came from Britain. The collection was British not by origin but by ownership and audience.

It was the first national museum that attempted to cover all fields of human knowledge. There were three departments: Printed Books; Manuscripts and Medals’ and Natural and Artificial Productions.

Gowin Knight, the first ‘Principles Librarian’ - the director - proposed that the collection should be organised alone the following lines:

‘things relating to Natural History [are to be]… classed in three general divisions of Fossils, Vegetables and Animals. Of these Fossils are the most simple; and therefore may be properly disposed in the first Rank; next to them the Vegetables and lastly the animal substances. By this arrangement the Spectator will be gradually conducted from the simplest to the most compound, and most perfect of nature’s production.”

There was no department of antiquities.

In 1735, the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus revolutionised the way plants, animals and other objects from the natural world were named and classified. His pupil, Daniel Solander, was a curator in the British Museum, and applied the system to Sloane's collections and to the natural history specimens that Solander himself collected with Sir Joseph Banks on the first Cook voyage.

The development of museums and the rationale behind displaying artefacts came to be informed by Enlightenment ideas about the absolute character of knowledge, understood to be something discoverable through rational inquiry and observation.

This approach can be seen today in the Enlightenment galleries of the British Museum today, a model of the 18th century Museum where the centre of this gallery of some 8,000 objects is the idea of classification.

Natural history reigned at the British Museum until 1772, when a collection of vases, bought from the collector and diplomat William Hamilton, signalled a blossoming interest in antiquities.

Sloane wouldn’t recognise any of the archaeological discovers of the 19th century that are in the museum today and which transformed European’s understanding of historical time.

As modern knowledge became to be about specialisation in the 19th century, the idea of collecting books and plants and manuscripts and curious artefacts under roof was rejected. The Natural History Museum, London, formed in 1881, is where you will find Sloane’s natural history specimens today.

The next post in the series on the roots of the culture wars in museums will look at ‘trouble in enlightenment’ - the rise of anti-enlightenment thinking in museums and its influence on contemporary controversies including that of the battle over the bones.